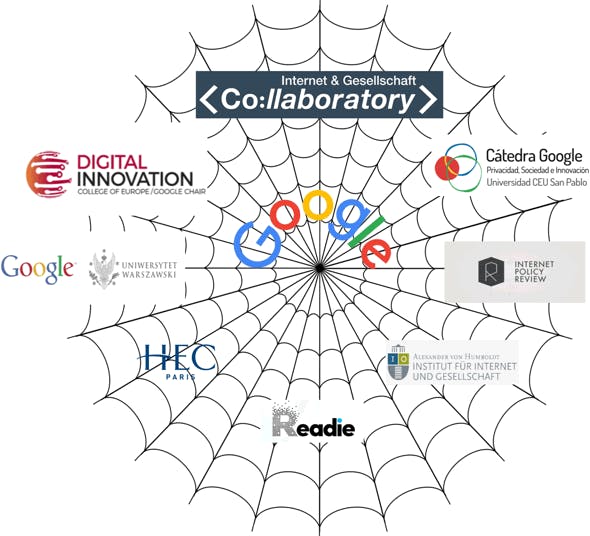

Over the past decade, Google has invested heavily in European academic institutions to develop an influential network of friendly academics, paying tens of millions of euros to think tanks, universities and professors that write research papers supporting its business interests.

Those academics and institutions span the length and breadth of Europe, from countries with major influence in European Union policymaking, such as Germany and France, to Eastern European nations like Poland.

Google-funded institutions have published hundreds of papers on issues central to the company’s business, from antitrust enforcement to regulation governing privacy, copyright and the “right to be forgotten.” Events organized by Google-funded institutions have attracted many of the European policymakers charged with creating and enforcing regulation affecting the company.

Google’s European program appears to be modeled on its extensive academic “AstroTurf” campaign in the United States, which CfA detailed in a July 2017 report, Google Academics Inc, and which was detailed in various press reports. However, new research has identified several significant differences in its European program. Taken together, they raise new questions about whether the European Commission has adequate procedures in place to prevent policymakers from being unwittingly influenced by Google’s proxies.

First, Google’s academic influence program in Europe has gone beyond funding existing academic institutions, as it does in the United States, to helping create entirely new institutes and think-tanks in key countries like Germany, France and the United Kingdom. In those countries, executives from Google’s lobbying operation have helped conceive research groups and covered most, or all, of their budgets for years after launch.

Google policy executives have acted as liaisons to steer their research priorities and host public events with policymakers.

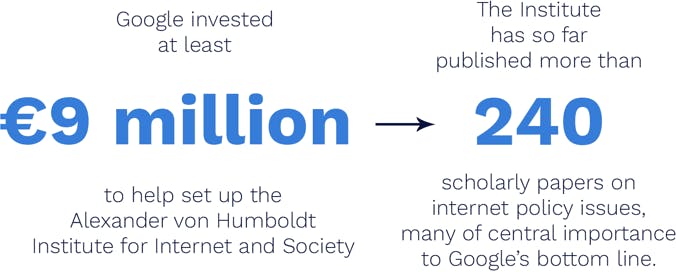

For example, Google has paid at least €9 million to help set up the Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society (HIIG) at Berlin’s Humboldt University. The new group launched in 2011, after German policymakers voiced growing concerns over Google’s accumulated power.

The Institute has so far published more than 240 scholarly papers on internet policy issues, many on issues of central importance to Google’s bottom line. HIIG also runs a Google-funded journal, with which several Google-funded scholars are affiliated, to publish such research.

The Institute’s reach extends beyond Germany, or even Europe. HIIG previously managed, and still participates, in a global Network of Internet and Society Research Centers to coordinate internet policy scholarship. Many are in emerging markets where Google is trying to expand its footprint, such as India and Brazil.

Google also helped establish and fund other similar bodies designed to influence public policies in other key European nations. In the United Kingdom, the company has funded the Research Alliance for a Digital Economy (Readie), which has hosted several policy conferences with European Commission officials and published dozens of articles and publications on policy issues important to Google.

In France, Google helped launch Net:Lab, a similar group that was set up to “provide an open platform for debate involving experts, policymakers and users” and “make concrete proposals to advance the societal, legal, academic and political debate” on technology issues.”

And in Poland, Google has funded the Digital Economy Lab (DELab) at the University of Warsaw, similarly described as an interdisciplinary institute that will research and design policies governing technology issues. Second, Google has created and endowed chairs at higher-learning institutions in European countries including France, Spain, Belgium, and Poland. Those chairs have often been occupied by academics with a track record of producing research that closely aligns with Google’s policy priorities.

Third, Google-financed research and Google-funded academics have become intertwined with research commissioned by the European authorities themselves. In one case, Google and the European Commission jointly financed a study by the Lisbon Council for Economic Competitiveness and Social Renewal that included arguments supporting less restrictive copyright and intellectual property rules, which Google favors.

In another, the European Commission commissioned academics from a Google-funded think-tank to make policy recommendations on whether regulation helps or hampers innovation. The research was cited in a subsequent European Commission policy paper. Such episodes raise questions about whether the European Commission has adequate procedures in place to mitigate potential conflicts of interest.

In Europe, Google has also replicated some of the tactics it has employed in the United States, where it has spent millions of dollars a year to produce favorable policy papers from universities like Stanford and Harvard, and from Washington think-tanks like the New America Foundation.

For example, Google started funding one of Brussels’ most influential think-tanks, the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), in 2014, as the Commission’s antitrust investigation of the company’s practices gained momentum. After Google became a corporate member of CEPS, the think tank’s scholars began participating in panels and publishing a series of policy papers opposing European Commission’s investigations of Google.

For instance, in January 2015, CEPS researcher Andrea Renda participated in a European Parliament forum entitled, “Will Internet monopolies rule our economy in the 21st century?” He opened his remarks by questioning the entire premise, asking: “What Internet monopolies?” Three months later he wrote a paper for CEPS entitled, “Antitrust, Regulation and the Neutrality Trap: A plea for a smart, evidence-based Internet policy.” The paper picked apart arguments by critics of Google that it should not be permitted to favor its own products.

CEPS has also hosted Google-friendly conferences for government leaders [See relevant articles here and here]. In November 2017, the think tank co-sponsored a forum with the EU’s assembly of local and regional representatives, the European Committee of the Regions, which included a paper by a CEPS fellow and former Google public affairs rep, Bill Echikson. Echikson’s paper touted job creation in Europe by Google and other tech companies, a top priority for the Committee at the time.

Europe’s importance for Google cannot be overstated. It is both a key market, with usage rates above 80 percent in many countries, and the most organized source of opposition to its expansion plans. The European Commission is arguably the only regulator beyond the U.S. with sufficient clout to cause Google to alter its conduct. European officials have levied billions of dollars in fines for antitrust violations and have enacted some of the most stringent laws in the world to protect consumer privacy.